2019 Post #30 -- The Poetry of Prose

by Travis Crowder

One of the beautiful things about poetry is that is touches all other genres. Poetry dwells within prose, both fiction and nonfiction, sometimes subtle and other times striking, but always trying to nudge us past the ostensible. Authors use poetic language to move their writing and to help us see the world through their eyes. Words, the molecules of ideas, envelope us, nudging us to think deeply about their function. Sometimes they seem to rest in the palm of an open hand, inviting us to use and to lean on them, to pull them into our own way of writing and speaking. This part of author’s craft is majestic, and I love introducing students to how authors use words to convey meaning.

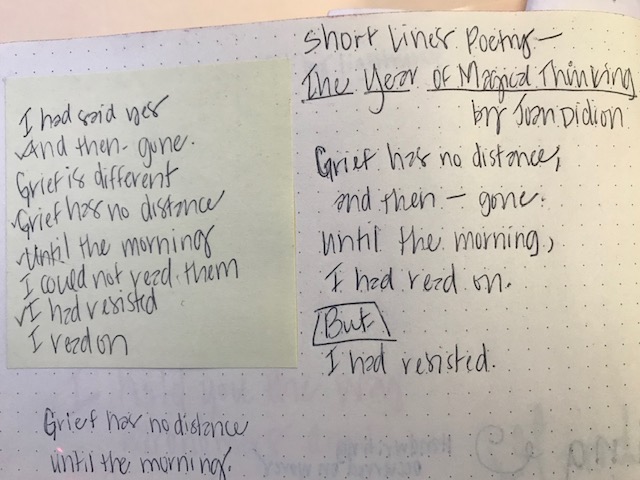

Just a few days ago, conversations about author’s craft centered around the use of short sentences in prose. I mentioned to students how powerful short sentences could be, but like many things in reading and writing, showing works better than telling. During independent reading, I asked them to collect short sentences (usually 1-4 words) form their books on sticky notes. I came to class with my own collection of short sentences from my book, The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion, pictured here:

Under the document camera, I began arranging the sentences into the form of a poem, paying attention to the meanings of lines, of how fractured sentences could be fused into new ones, of how meaning changes when lines are extracted from context and blended with something else. As I arranged the sentences, I thought aloud, telling students that adding or removing words from the original sentences was acceptable.

After a few minutes of crafting in front of them, I invited them to do the same. Students worked for about ten minutes with the sentences from their independent reading. During this time, I asked them to mold them into the shape and feel of a poem, read it aloud to themselves, then revise their original poem by swapping lines, interspersing their own lines of original thought, isolating words on a single line to draw attention to them, and so on.

After collecting short sentences from Girl in Pieces by Kathleen Glasgow, Levi wrote:

The arrangement of sentences—filled with haunting lyricism—mesmerized me and his other readers.

Brittany, while reading Flawed by Cecilia Ahern, found this poem of sentences:

The blend of dialogue gives her poem a different edge. Characters’ names were in the original version, but I encouraged her to remove them so the reader could create the voices and names.

Finally, students shared their poems with a classmate and posted it on a class Padlet. I also shared mine.

I asked students to tell me how their thinking had changed about short sentences. They answered, “We had no idea short sentences could be so powerful.”

And now, they have beautiful poems and a method of reflection that they can return to again and again.

One of the beautiful things about poetry is that is touches all other genres. Poetry dwells within prose, both fiction and nonfiction, sometimes subtle and other times striking, but always trying to nudge us past the ostensible. Authors use poetic language to move their writing and to help us see the world through their eyes. Words, the molecules of ideas, envelope us, nudging us to think deeply about their function. Sometimes they seem to rest in the palm of an open hand, inviting us to use and to lean on them, to pull them into our own way of writing and speaking. This part of author’s craft is majestic, and I love introducing students to how authors use words to convey meaning.

Just a few days ago, conversations about author’s craft centered around the use of short sentences in prose. I mentioned to students how powerful short sentences could be, but like many things in reading and writing, showing works better than telling. During independent reading, I asked them to collect short sentences (usually 1-4 words) form their books on sticky notes. I came to class with my own collection of short sentences from my book, The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion, pictured here:

Under the document camera, I began arranging the sentences into the form of a poem, paying attention to the meanings of lines, of how fractured sentences could be fused into new ones, of how meaning changes when lines are extracted from context and blended with something else. As I arranged the sentences, I thought aloud, telling students that adding or removing words from the original sentences was acceptable.

After a few minutes of crafting in front of them, I invited them to do the same. Students worked for about ten minutes with the sentences from their independent reading. During this time, I asked them to mold them into the shape and feel of a poem, read it aloud to themselves, then revise their original poem by swapping lines, interspersing their own lines of original thought, isolating words on a single line to draw attention to them, and so on.

After collecting short sentences from Girl in Pieces by Kathleen Glasgow, Levi wrote:

I am alone.

In the house.

I let them pull me in.

Deep down.

Black as night.

Nothing in my mind.

I turn it off.

I stare at the computer.

Years goes by.

But I am not.

....... died.

In my mind.

I feel free.

But in my heart.

I am gone

The arrangement of sentences—filled with haunting lyricism—mesmerized me and his other readers.

Brittany, while reading Flawed by Cecilia Ahern, found this poem of sentences:

A light goes on for me.

I have people.

My hearing is this afternoon.

She makes a face.

I smile at her in thanks.

And then we are inside.

He tips his hat.

¨Do you agree?¨

I silently fume, then think hard.

¨Absolutely.¨

The room erupts.

I jump up.

I pass out.

The blend of dialogue gives her poem a different edge. Characters’ names were in the original version, but I encouraged her to remove them so the reader could create the voices and names.

Finally, students shared their poems with a classmate and posted it on a class Padlet. I also shared mine.

Grief was different.

an ocean of dark

I could not read.

I had resisted,

but soon said yes,

and felt the rush

of numbing waves.

Grief has no distance

until the morning,

when streams of light

streak the sky.

Stretching Their Thinking

Creativity exploded with this activity. I wanted students to deepen their awareness of the utility of short sentences while also appreciating author’s craft. After students posted their poems on the Padlet, I gave them time to read their classmates’ poems, identifying the one they were drawn to the most. Inside their notebooks, they copied the poem and wrote their why: What caused them to choose this poem? What word or line stands out the most to them? How does this poem make you feel? Time was provided to share poems that resonated and to celebrate their craft. I asked students to tell me how their thinking had changed about short sentences. They answered, “We had no idea short sentences could be so powerful.”

And now, they have beautiful poems and a method of reflection that they can return to again and again.

Further Reading:

Travis Crowder is a 7th grade ELA teacher in Hiddenite, NC, teaching ten years in both middle and high school settings. His main goal is to inspire a passion for reading and writing in students. You can follow his work on Twitter (@teachermantrav) and his blog: www.teachermantrav.com/blog.